History always seems to leave its deepest imprint where rivers meet. A confluence, thus, is never only about geography—it is where faith gathers, trade routes entwine, and kingdoms etch destinies. In Assam, we witness this at Kajalichaki or chowki, about 35 km from Guwahati towards Mayong and Pobitora, where the restless waters of the mighty Brahmaputra embrace those of the swifter Kolong,

A solitary hillock, rising commandingly from the vast floodplains, Kajalichaki, as it is known, stands as a keeper of history and legends. Once the second most formidable defence outpost of the Ahom kingdom after Guwahati, myths and stories flow like the rivers at its feet. A silent sentinel of centuries of valour and vigilance, built of earth, stone, and strategy, it echoes the tragic legend of Jungal Balahu, the Tiwa king whose strength—believed to have rested in a divine sword—was stripped away by his wife, who, conspiring with her father King Gajraj, hid the weapon inside a humble catfish. Shorn of might, Balahu plunged into the Kolong where, ironically, on the very log dam he had once built, Kachari soldiers speared him to death. Even now, remnants of his stone fish-traps linger by the riverbank, weathered but determined to keep the Balahu legend alive.

History too carved its own deep mark on Kajalichaki. During the reign of Ahom king Swargadeo Pratap Singha (1603–1641), the outpost rose in strength, girdled with embankments that linked river to temple, village to frontier, earth to empire—through Kajali to the Vishnu temple, onward to Govardhan along the Kolong, and then south from Hatishila to Digaru. Stockades of bamboo and earthen walls became a shield and a lifeline, holding back invaders while sustaining supply lines. Surrounded by ramparts with a sweeping view of the Brahmaputra’s vast waters and a moat wide enough to shelter war boats, Kajalichaki came to be established as a military headquarters in the early 17th century, governed by two Kajalimukhia Gohains, wielding both civil and military authority.

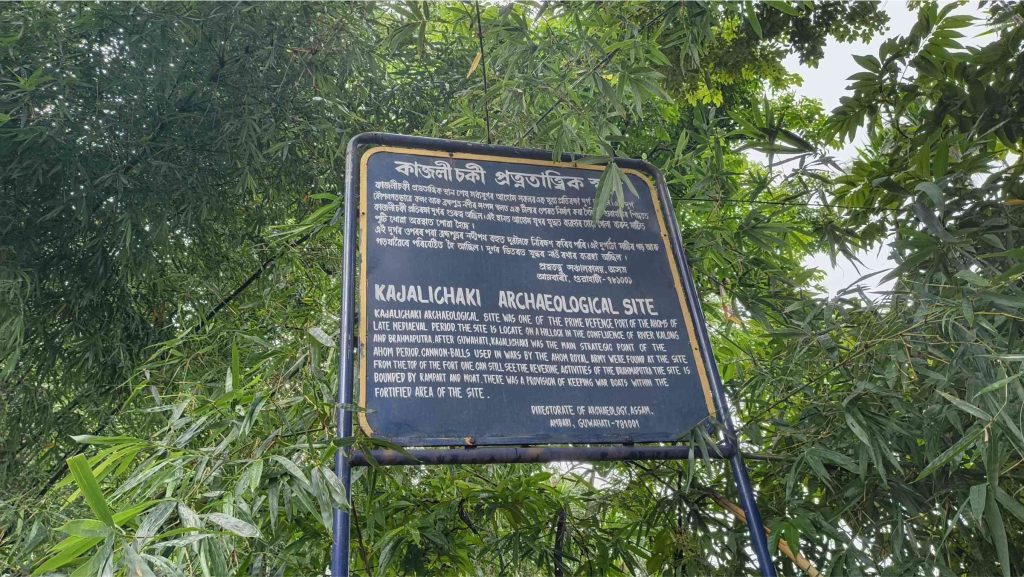

Today, you espy the confluence and the solitary hillock shimmering in the sun soon after you cross Kajalichaki Bridge over the Kolong. A gentle climb up its steps at the Kajalichaki Archaeological Site (about 35 km from Guwahati) takes you to the hillock’s crest and a stirring view—the Brahmaputra still restless, the Kolong still swift, as if time has not moved. An iron-grilled vault nearby holds a handful of cannonballs, all heavy with memory of a land-water theatre of war against Mughals, Jayantias, and Kacharis. Other weathered spheres once hurled in the fury of battle rest in the Mayong Village Museum and Research Centre at Roja Mayong,,each a relic of remembrance of warriors who defended the frontier. Standing where warriors once kept watch, walking the embankments where kingdoms clashed, and then looking beyond to where the confluence appears kajali (blackish), two rivers joining in colours that never quite merge, is experiencing a heritage landscape, where memory lingers in cannonballs, moats, and myths. Here, history speaks not through any ruin, but through stones, water, wind, and whispers of Assam’s enduring story.