Travelling through Assam, you first meet tea gardens rolling like green waves, the mighty Brahmaputra flowing with quiet grandeur, and forests alive with rare wildlife. Linger a little, and another Assam emerges—one of silent giants rooted in earth and memory. These are the state’s heritage trees: approximately more than a hundred of them, each over a century old and some as ancient as 600 & 500 years, lovingly chronicled by the Department of Environment and Forest in Heritage Trees of Assam.

Heritage tree tourism is not about ticking off sights; it is about meeting these elders of the natural world. Recognised for their age, size, rarity, or cultural resonance, here they grow beside Ahom-era temples, stand sentinel at satras and royal palaces, and form the heart of villages where folk tales still breathe beneath their shade.

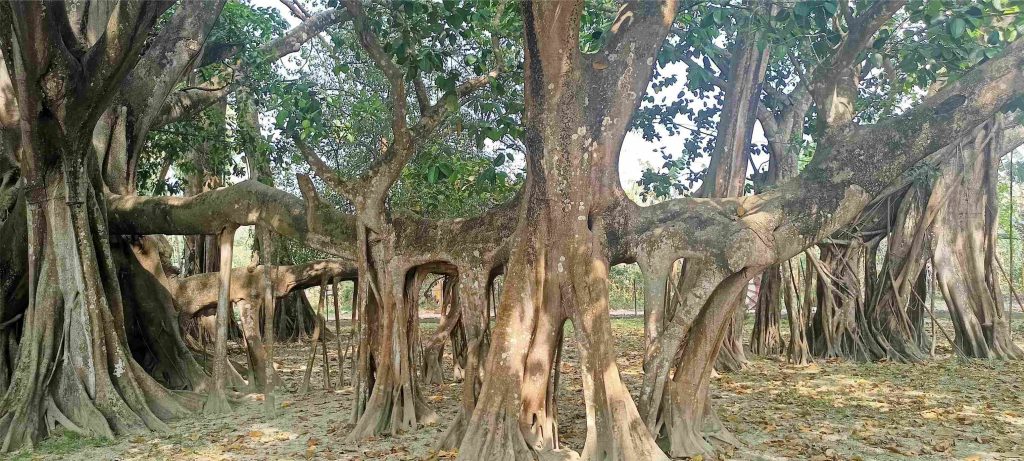

Consider the Ghila of Golaghat, an African Dream Herb that has stood for nearly six centuries. In Barpeta, a 500-year-old Ahot (Peepal) still shelters devotees and storytellers. Kendu, the East Indian Ebony of Kenduguri, Joypur in Dibrugarh and the fragrant Bakhor Bengena (Divine Jasmine) of Sivasagar, both around 500 years old, keep alive the memory of the Ahom dynasty. Across the state are others just as venerable: the Bor / Bot (Banyan) of Dhekiakhowa Bor Naamghar at Jorhat sheltering prayers for nearly five centuries; the Teli- Kodom (Kadamba) planted near Srimanta Sankardeva’s Thaan in Barpeta, still flowering after 400 years; the Bakul of Bajali and the Korai (White Siris)of Chirang, each holding sacred associations. The Aam (Mango) of Sirajuli Satra, the Paroli (Yellow Snake Tree) of Lakhimpur, the Bel (Wood Apple) of Sivasagar, all around 400 years old, create a living timeline of Assam’s history and folklore.

Younger but equally fascinating trees—banyans, tamarinds, mangoes—between 300 and 100 years old thrive in temple courtyards, satra premises, tea estates, and village commons. The 300-year-old tamarinds of Morigaon, the 200-year-old banyans of Majuli, and the 100-year-old neem of Kasturba Gandhi Ashram in Guwahati together show that heritage is not only ancient—it keeps growing.

These trees are more than botanical marvels; they are woven into Assam’s culture. At the satras of Majuli, they frame monuments and festivals. In village commons, they are gathering points for Bihu celebrations. In forests and tea estates, they protect biodiversity, stabilize soil against erosion, and provide refuge to countless birds and insects.

For travellers, they open new paths of exploration. By weaving heritage tree visits into Assam’s tour itineraries, a journey from Guwahati to Majuli might include resting beneath a banyan that has witnessed centuries of prayer, or a drive to Manas National Park could be paused near Pathsala’s Kalibari Thaan also known as Jalikatha to see 210-year-old banyan where nature, spirituality, and community life meet. Standing beneath these giants, touching their gnarled barks, listening to rustling leaves, and feeling the pulse of a land that measures time in centuries, is an act of slowing down. Heritage trees educate, support local livelihoods, and inspire conservation. As Legend Zubeen Garg would often say, the truest tribute is in planting and saving a tree—a living legacy that will outlast us all.

Note: The article draws inspiration from Heritage Trees of Assam, a pictorial coffee table book published by the Government of Assam through the initiative of the Silviculturist, under the Environment and Forest Department.